The AS Hindenburg, like RMS Titanic, was not just one ship, but one of a class of ships. The Hindenburg was the lead ship of the Hindenburg class of airships ( AS ), the second and last of the Hindenburg class was the AS Graf Zeppelin. The Graf Zeppelin was never operated on regular passenger service. In 1940, Hermann Goringordered the Graf Zeppelin scrapped and the aluminum was used for aircraft production.

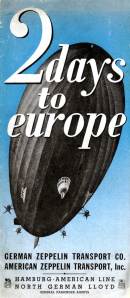

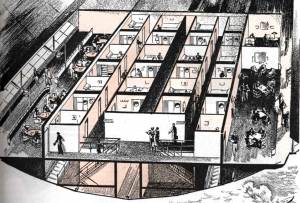

Though there have been ships since the Titanic that were larger, more powerful, and with better passenger accommodations, Titanic retains the mystique as the best of the best. The Hindenburg was the best airship of her era, and of all time. No other airships have been built that can compete with the size and accommodations of the Hindenburg. The Hindenburg was 804 feet long (245 meters) and 135 feet in diameter (41 meters), almost as long as and wider than Titanic.

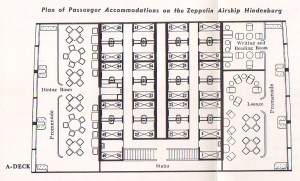

Hindenburg, hull number LZ-129, was designed to carry 40 passengers and 50 crew, using helium for its lift gas. The United States controlled the world’s largest supply of helium, and would not export the gas to NAZI Germany. The Hindenburg had to be redesigned for hydrogen gas. This change allowed an increase in passengers from 40 to 72, due to the increased lift of hydrogen over helium.

Construction on LZ-129 began in 1931, but the dream of this magnificent airship goes back to 1924. After World War One all German airships were demanded as war reparations. Count Von Zeppelinpioneer of rigid airships, and founder

of the Zeppelin Company, died in 1917. Dr. Hugo Eckener became the chairman of the company. Eckener saw dirigibles as ships of peace, not war. In 1919, Eckener’s first two post-war dirigibles took flight. In 1921, the allies demanded them as war reparations as well. However, Eckener and the Zeppelin Company were not ready to admit defeat. Their next chance came in 1924. The Americans had one dirigible of their own, the Shenandoah, and purchased one from the United Kingdom, R-38. When R-38 exploded in a test flight, Dr. Eckener seized the opportunity. The Zeppelin Company had an order. The Germans were forced to pay for the construction of the new zeppelin as continuing war reparations, but Eckener was building dirigibles again.

Zeppelin company engineer Dr. Durr, using all the technological expertise gained from World War One, designed the most technologically advanced dirigible designed up to that time. LZ-126 took its first test flight on 27 August 1924. To deliver LZ-126 to the Americans the Zeppelin Company had to fly the airship 5,000 miles and across the Atlantic ocean. No insurance company would issue a policy to the Zeppelin Company. If LZ-126 did not complete the journey, the cost would destroy the Zeppelin Company. Dr. Eckener took the controls of LZ-126 and flew the airship to American himself, in 81 hours.

In America, large crowds met the LZ-126 on its arrival. Dr. Eckener and his crew were invited to the White House, where President Coolidge called the new zeppelin an “angel of peace.”

Due to the post-war economy in Germany, it was another two years before the Zeppelin Company acquired the needed funds to build LZ-127. Christened the AS Graf Zeppelin, Dr. Eckener intended to use the airship for demonstrations and experiments, while designing a fleet of rigid airships that would carry passengers and mail.

In 1929, the Graf Zeppelin became the first dirigible to circumnavigate the world, completing the trip in 21 days and 5 hours. With many more trips to different places around the world, including a research trip to the arctic, Dr. Eckener decided it was time to begin the design of LZ-128. The explosion of a British passenger airship caused Eckener to cancel LZ-128. The idea of Hindenburg was born.

Eckener decided to design a new airship that would not use the explosive hydrogen for its lift gas; instead, LZ-129 would use the inert gas helium. Helium did not have the lift that hydrogen did, but helium would not explode. Unfortunately, helium was the first of many problems LZ-129 would have due to politics, both inside and outside of Germany. Helium was a rare by-product of natural gas reserves in the United States. The United States banned the export of helium to Germany as a material of “military value.” Dr. Eckener thought he could persuade the Americans to supply helium for LZ-129, but they would not be persuaded. So, LZ-129 was redesigned to use hydrogen for its lift gas. The redesigned did allow the passenger capacity of LZ-129 to be increased from 40 to 72 passengers. Then the Zeppelin Company went bankrupt in 1931, and construction of LZ-129 stopped.

Dr. Eckener, an avid anti-Nazi, was forced to make a deal with the Nazi party for funding. As a result, he completed LZ-129, but was forced to put the Nazi symbol on the tail fins. Construction resumed in 1935, with the construction of LZ-130 beginning in 1936. This was only the first of many battles Dr. Eckener would have with the Nazi’s. Because of Dr. Eckener’s continued refusals to cooperate with the Nazi’s, Hermann Goring (the German Air Minister) formed a new airline in 1935 and took over operation of airship flights. These battles continued between Eckener and the Nazi’s, while at the same time many around the world saw the Zeppelin Company’s dirigibles as a symbol of the Nazism.

Overhead drawing of Hindenburg. Author’s collection. This drawing is copyrighted by David Fowler. for an updated version see his web site http://www.airships.net

On 4 March 1936, LZ-129 left on its maiden voyage with 87 passengers, crew, and Dr. Eckener as the commander. On LZ-129’s second flight the mayor of Munich asked the name of LZ-129 via radio. Eckener replied, “The Hindenburg”. Eckener had chosen the name, honoring the German President, over a year earlier but had kept the name quiet. Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels was furious, he ordered Dr. Eckener to be in Berlin the next day. Goebbels ordered Eckener to change the name of LZ-129 to Adolph Hitler, and Eckener refused. Goebbels then decreed that in Germany the Hindenburg would be known only as LZ-129. Eckener also refused to endorse Hitler or Hitler’s policies in the election campaign and continued to oppose using the LZ-129 and LZ-130 for propaganda purposes. Goebbels also told Eckener he had the power to make Eckener (a world famous aviator) a non-person in the German media. Eckener still refused and Goebbels decreed that Eckener was not to be named, mentioned, or otherwise referred to in the German media, including photographs and articles.

On 31 March 1936, Hindenburg left on its first commercial flight. By this time, the German Air Ministry had removed Eckener as the commander, leaving him with no operational control over the Hindenburg. On this first flight, Hindenburg lost an engine before arriving in Rio de Janeiro. The Hindenburg lost another engine on the return flight threatening the loss of Hindenburg near Morocco. However, the crew found favorable trade winds lower than they should have been saving the airship. The engines were rebuilt on arrival and the Hindenburg had no further engine problems. The Hindenburg completed 17 trips to North and South America in its first year.

The Hindenburg completed its first South American trip of the season in March 1937. On 3 May 1937, the Hindenburg

Uniform for LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin & LZ 129 Hindenburg, c 1935. Exhibit in the Zeppelin Museum Friedrichshafen, Seestraße 22, Friedrichshafen, Germany. Photography was permitted in the museum, without restriction. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

left for its first North American trip of the season. Strong head winds slowed the speed of what was an otherwise normal voyage. LZ-129 Arrived at Lakehurst, New Jersey from Frankfurt, Germany on 6 May 1937. After a delay of several hours because of thunderstorms, the Hindenburg was given clearance to dock at 7:00 PM. At 7:25, four minutes after the handling lines had dropped from the nose of the airship. Hindenburg suddenly burst into flames and dropped to the ground in just 37 seconds. On board were 36 passengers and 61 crew, 13 passengers, 22 crew, and one ground handler died in the disaster. The cause of the fire has never been conclusively determined and remains controversial to this day.

Witnesses saw a flutter in the fabric ahead of the upper fin as if gas were leaking. Other witnesses saw blue discharges, both just before the fire. There were several cameras on the scene, but none were rolling when the fire started. However, from the eyewitness accounts the fire seems to have started around gas cell number four.

There have been many theories about what caused the disaster, which will be briefly mentioned below:

SABOTAGE: This was the most common theory at the time of the disaster. Dr. Hugo Eckener believed this theory at first. However, after learning that the Hindenburg burned instead of exploding, he favored the static discharge theory. Commander Charles Rosendahl, commander at the Naval Air Station Lakehurst and in charge of the ground operations for landing the Hindenburg believed it was sabotage and said so in his 1938 book What About the Airship?, which covered the history and his proposed future of rigid airships. The commander of the Hindenburg, Max Pruss, also believed this theory. There have been several books on this theory, some even naming suspects. The 1975 movie The Hindenburg (starring George C Scott and Anne Bancroft) based on MacDonald Mooney’s book by the same name, identified crew member Eric Spehl as the saboteur (Mr. Spehl died in the disaster).

The reasons for sabotage have also been numerous. From pro-communists to anti-Nazi’s, some even believe the Nazi’s sabotaged the Hindenburg to gain sympathy for their cause.

STATIC DISCHARGE: This was Eckener’s theory and seems the most likely. A build up of static electricity due to the thunderstorms that had delayed Hindenburg’s docking, may have been discharged when the mooring lines fell down from the airship touching the ground. This effectively electrically grounded the frame of the airship, but not the skin of the airship. A spark jumping between the skin and the frame could have then spark hydrogen gas causing the fire. This theory has many supporters including experts.

LIGHTNING STRIKE: A.J. Dessier, former director of the Space Science Laboratory at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center believes this theory. The Hindenburg had been struck by lightning many times before, but hydrogen needs to be mixed with oxygen to ignite. Hydrogen in the gas cells is free of oxygen. Though, at the time Hindenburg was landing and would have been venting small amounts of hydrogen as part of ballast control during landing operations. This vented hydrogen would have been vented into the air and could have ignited along the top of the airship.

ENGINE PROBLEMS: Hindenburg did have engine problems on its maiden voyage the year before. A ground crew member saw a shower of sparks from an engine as it was slammed into reverse during the docking. First the vented hydrogen would have been vented along the top of the airship, and floated up. The engines under the airship were not in a position to provide the ignition source for the fire. Second, hydrogen ignites at 700 degrees C (1,290 degrees F) but the sparks would only reach a temperature of 250 C (480 F).

INCENDIARY PAINT: This theory was also proposed by a retiree from NASA, Addison Bain. Bain believed that the doping compound used to coat the fabric of the skin was the cause of the fire. There have been television specials in recent years, which support this theory. AJ Dessier (see lightning above) believes this was not possible and has made a very good case against this idea.

HYDROGEN LEAK: The Hindenburg was stern heavy during docking. Which this theory states is because of a hydrogen leak which released hydrogen into the air inside the frame of the airship.

CONCLUSION: There are still more theories. However, these are the most commonly accepted theories. The most likely cause of the disaster is a static discharge along the top of the Hindenburg or a lightning strike.

The Zeppelin LZ 129 Hindenburg catching fire on May 6, 1937 at Lakehurst Naval Air Station in New Jersey. (Photo credit: Wikipedia)

To learn more about the Hindenburg go to the following web site: www.airships.net/hindenburg (this is probably the best site on the web for Hindenburg information) or you can visit the Zeppelin Museum: www.zeppelin-museum.de/ or in English at www.zeppelin-museum.de/home_en.0.html

You can also check out the book, “Hindenburg: An Illustrated History”

Related articles

- 75 Years Ago Today: Lakehurst, New Jersey, 6 May 1937 (joeccombs2nd.com)

- The Hindenburg Disaster (vintag.es)

- From the archive, 8 May 1937: Hindenburg airship disaster leaves 33 dead (guardian.co.uk)

- Markets, Risk, and Fashion: The Hindenburg’s Smoking Lounge (american.com)

- Airships live on, 75 years after Hindenburg disaster (news.cnet.com)

- LiveLeak.com – Hindenburg Disaster – Stabilized HD (tribuneofthepeople.com)

- Reflecting on Hindenburg disaster 75 years on (thelocal.de)

- Images keep memory of Hindenburg alive (abc.net.au)

- Flashback Fridays: Akron, Another Ohio Aeronautical Landmark (blogsouthwest.com)

- The Hindenburg piano (bibliolore.org)

Nice article. I notice, however, that the source of the image, “Overhead drawing of Hindenburg” is listed as “Author’s collection.” Please note that although it is reduced and difficult to read, my copyright notice is still present in the upper left and right corners. I assume this version was copied from Airships.net where it is properly credited and used with my permission. Also, please note that this version of the drawing has been superseded by one with additional detail and minor corrections.

David Fowler

LikeLike

Mr. Fowler after reading your comment I took my framed copy of that image down from my wall and out of its frame (it was a gift to me framed). You are most correct sir, and I apologize for the ommission. I will correct it. You have an outstanding web site and I was very pleased to tell my rreaders about your web site.

LikeLike

Here is a link to more on the Hindenburg on another blog. http://wp.me/p2s0SG-2Is

LikeLike

thanks for continuing to read my word-I always learn from your blog-you do a lot of research! beebeesworld

LikeLike

Thank you. And thank you for your posts, you will never know how much they have helped me. Thank you.

LikeLike

Good info. Lucky me I ran across your site by chance

(stumbleupon). I’ve saved as a favorite for later!

LikeLike

This is awesome!

LikeLike

Hebert Morrison’s emotional radio commentary of this disaster still gets me.

LikeLike

me too

LikeLike

Whoops, make that HERBERT Morrison. Sorry, I didn’t have enough caffeine yesterday. 😉

LikeLike

Interesting article-thanks for reading my blog, I hope you will follow me. I will follow your blog as well. Thanks!

LikeLike

This is such an interesting read and a fascinating subject.

LikeLike

Thank you. I have been interested in the Hindenburg since I was a child. I did not think many other people would be, but I was wrong

LikeLike